Good challenges vs. bad challenges (Etsy last lecture)

This is a slightly modified version of my Etsy last lecture, given September 9, 2019 during my last week at Etsy. Last lectures are an (optional) Etsy tradition in which departing employees share parting wisdom with their coworkers. There aren’t really any rules, prescribed topics, or required levels of polish for a last lecture; it’s up to the lecturer to decide what they think is important to share during their hour. I decided to share some raw thoughts about dealing with challenges, and thought I’d share it here with you.

Hi! For those of you who don’t know me, my name is Jessica Harllee and for the next two days I’m a staff product designer on the Core Buyer team. I’ve been at Etsy for five and a half years. And this is my last lecture.

My favorite last lectures are the ones that are full of stories, and are really open and honest. I’m going to do my best to do the same here. This means I’m going to be telling some stories about things that have been really hard for me here. It’s really, really important that you know that this is not a laundry list of reasons why I’m leaving Etsy. If anything, these are the reasons why I’ve stayed at Etsy for so long.

I wanted to talk about something that’s been on my mind for the past six months.

If you want to learn and you want to grow, you need to challenge yourself. You have to get out of your comfort zone and try something you’ve never done, or that you didn’t think you could do. Learning is supposed to be a little uncomfortable, otherwise you’re not learning. It’s supposed to be challenging.

How do you know if something is the good kind of challenging (pushes you to grow and stretch) versus the bad kind of challenging (not something you can/should do)?

— Jessica Harllee (@harllee) April 16, 2019

But how do you know when something is the good kind of challenging versus the bad kind of challenging? You know what I mean? Like, there’s the kind of challenging that really pushes you, and you come out the other side even stronger and wiser than before. You feel capable of anything. And then there’s the kind of challenging that is nearly impossible to overcome. It brings you down a notch. It feels bad. Without challenges, we don’t grow or develop new skills. But not all challenges should be treated equally.

I’ve been in search of the answer to this because I’ve been through a bunch of challenges recently, and I didn’t have a nice framework in my mind where I could easily be like, this challenge is good! Just stick it out! Or, this challenge is bad! Get out now before it destroys you!!

So to answer this question, I thought I’d reflect on a bunch of challenges that I’ve encountered over the past few years in my career. Maybe some of these challenges will be similar to challenges that you’ve encountered, too. And hopefully by the end of this, you too will have a framework for understanding what’s a good challenge, and what’s a bad challenge.

A quick note: I’d be remiss if I didn’t acknowledge the fact that I experience many privileges, and that overall, I’ve felt very safe in my job here. All of that dictates how I’ve been able to respond to challenging situations, and more importantly, how other people have responded to me. I’m sharing what worked for me when I was faced with challenges, but I also recognize the role that privilege plays in that.

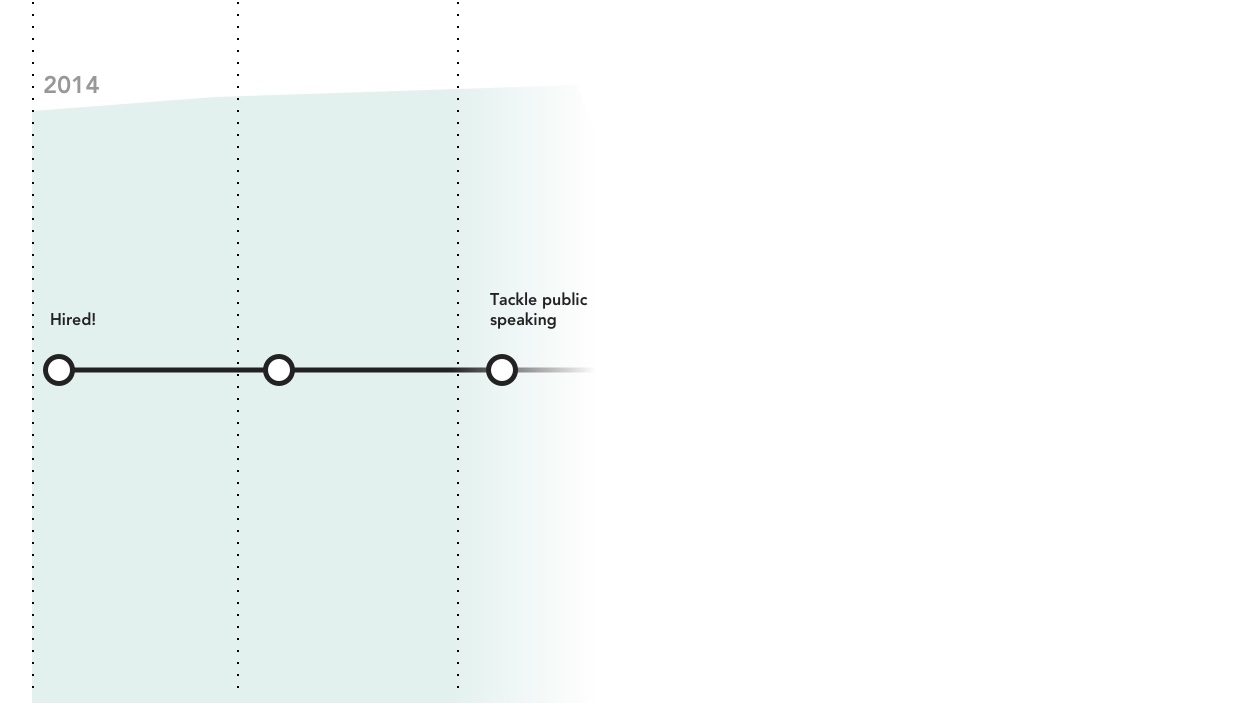

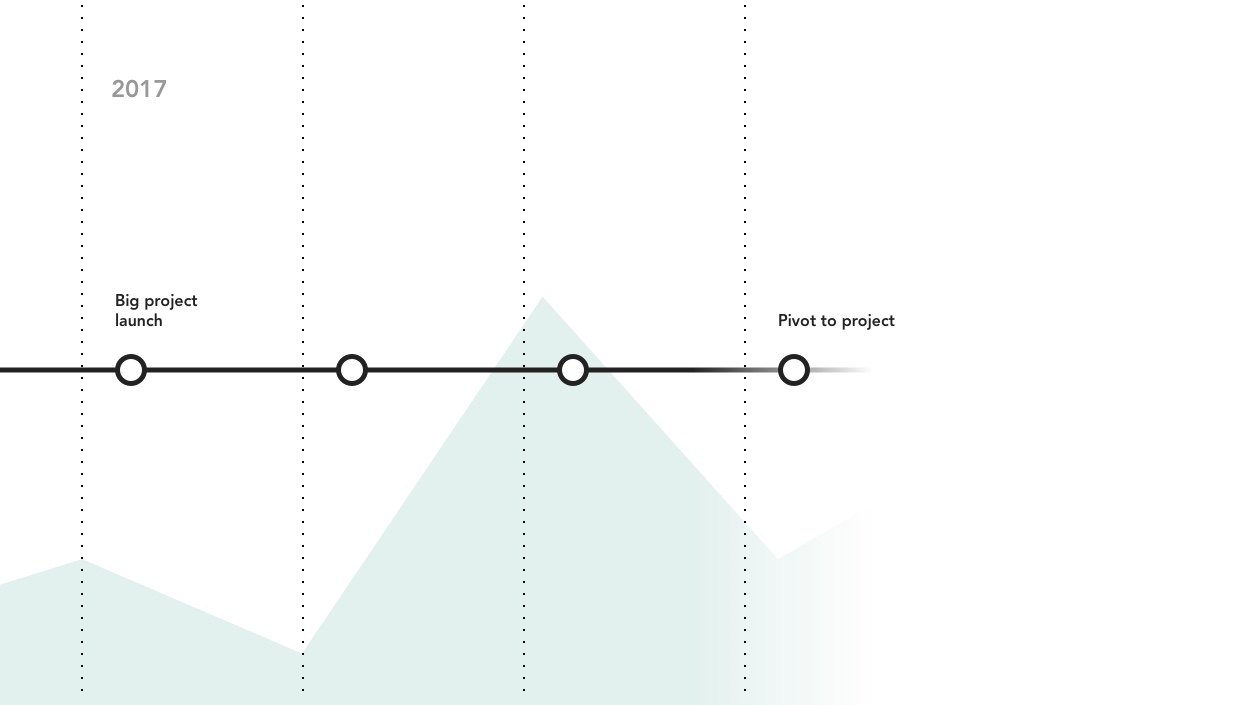

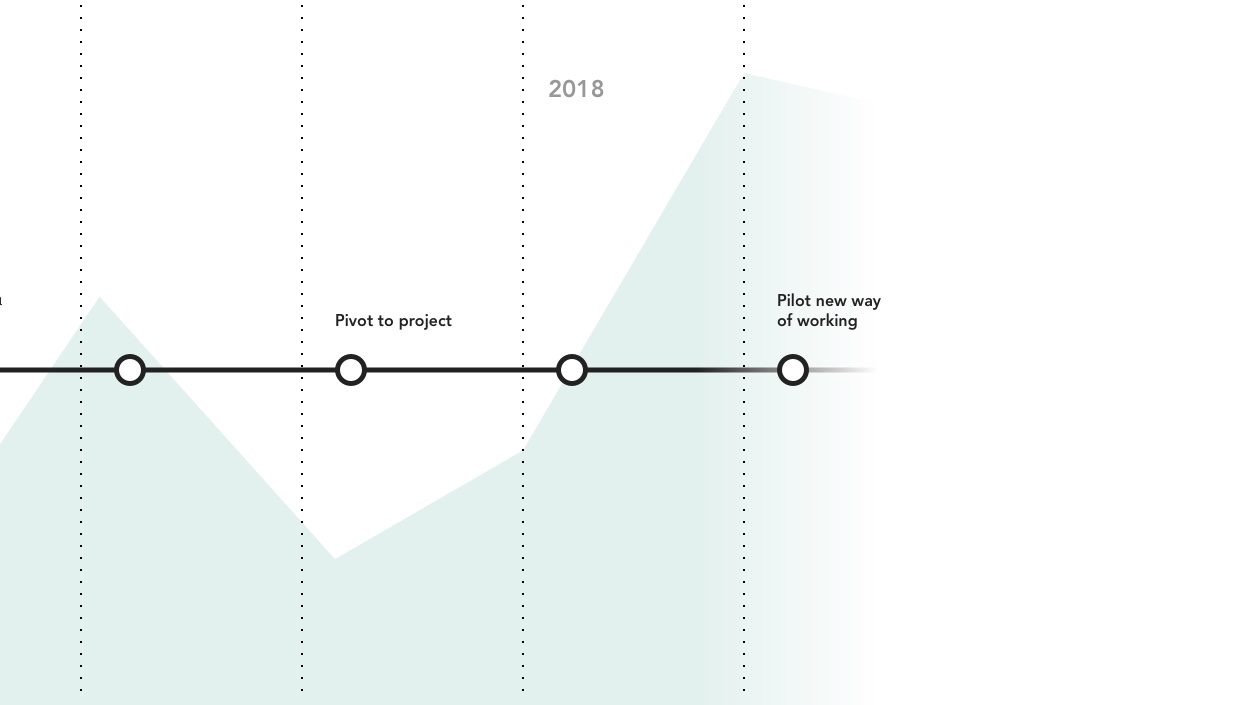

(Yes, I made a journey map of my time at Etsy.)

Challenge: Get over my fear of public speaking

Let’s start with 2014. A few months into working at Etsy and I was learning so much about design. I had all of this energy, and I wanted to share it. It felt like everyone around me was getting into public speaking. I saw designers I admired giving amazing talks. Everyone at Etsy was speaking, too. I loved it. I wanted to be a part of it. But the idea of speaking in front of people on a stage completely terrified me.

So, I decided that it was time to get over my fear of public speaking. My manager, Cap, was frequently speaking at conferences, and I told him that I also wanted to get into public speaking. He often found himself with more invitations to speak than he could manage. So whenever an opportunity came along that he couldn’t make, he passed it along to me, helped me prepare for it, and gave me feedback along the way. I went from having no public speaking experience to giving 6 talks in a year.

This was the good kind of challenging. I was developing an important skill that I wanted to learn. I had a manager coaching me through the process and a supportive team that listened to my bad drafts and gave critical feedback. Most importantly, I hit a point where it no longer terrified me. It’s how I’m able to stand here right now before you and feel (mostly) calm. I conquered my fear.

This was one of the first examples of sponsorship that I had ever experienced. I identified a skill that I wanted to develop, and put it out into the world by sharing it with my manager. He used his access to find me opportunities to develop this skill, and supported me along the way. I probably could have made it work on my own by submitting proposals and cold-emailing people, but I think that I ended up being so much more successful because my manager supported me.

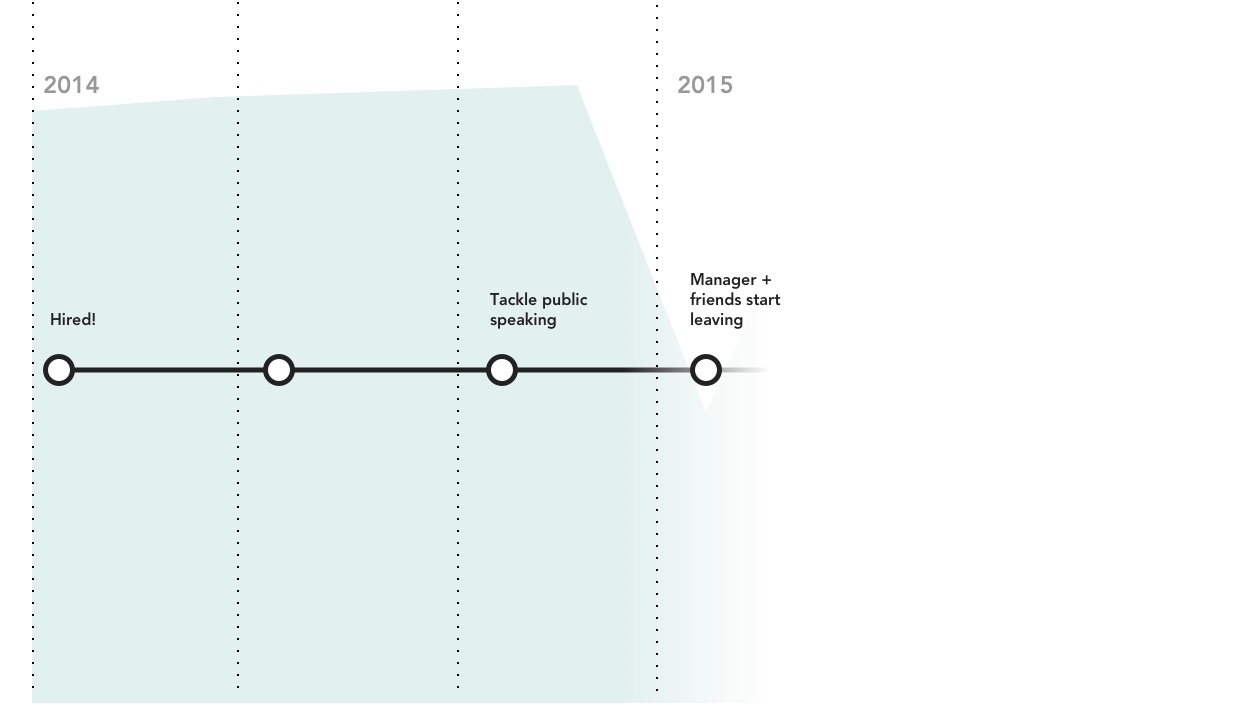

Challenge: Everyone is leaving

It’s 2015. I was a year into my job at Etsy. I’d spent it working on a project that I loved with a team that I loved. For the first time at a job, I felt really, deeply supported. Things were going great.

And then, my manager, Cap, quit. Shortly after that, the most senior designer on my team, Aaron, quit as well.

It felt like such a blow. I was so bummed out. Cap had done so much to teach me about design, and collaboration, and had coached me on my writing and my public speaking. And Aaron had brought me into developing Etsy’s very first design system, the web toolkit, and I had learned so much from him in the process. Not to mention, I really valued and trusted their opinions. If they were leaving Etsy, were things bad? Did they see something I didn’t? Should I leave?

At previous jobs, when people I respected left, I was almost always like, oh shit gotta get out of here! But I was really happy with my job at Etsy, like happy in a way I had never been at a job before. I didn’t want to leave. I honestly had no good reason to leave, other than my own fear of change. So, I made the decision to stay.

And, I quickly learned that a side effect of people leaving is that it gives others the chance to step in and fill the gaps that those people leave behind. With Aaron leaving, I’d have an opportunity to be in more of a leadership role on the web toolkit work. So I decided to go for it, and to fill that gap. I felt ready.

This ended up being the good kind of challenging. Before working at Etsy, I was really terrible at dealing with change, so much so that I got feedback in my first annual review about it. I thought that all change was bad and didn’t have the tools or resiliency to deal with uncertainty.

I reflected on this situation a lot in my time here and how it would have been such a shame if I had left after being here for only a year, and how much I would have missed out on. By pushing through something that was hard and dealing with it instead of running away, I also showed myself that I was tougher than I thought.

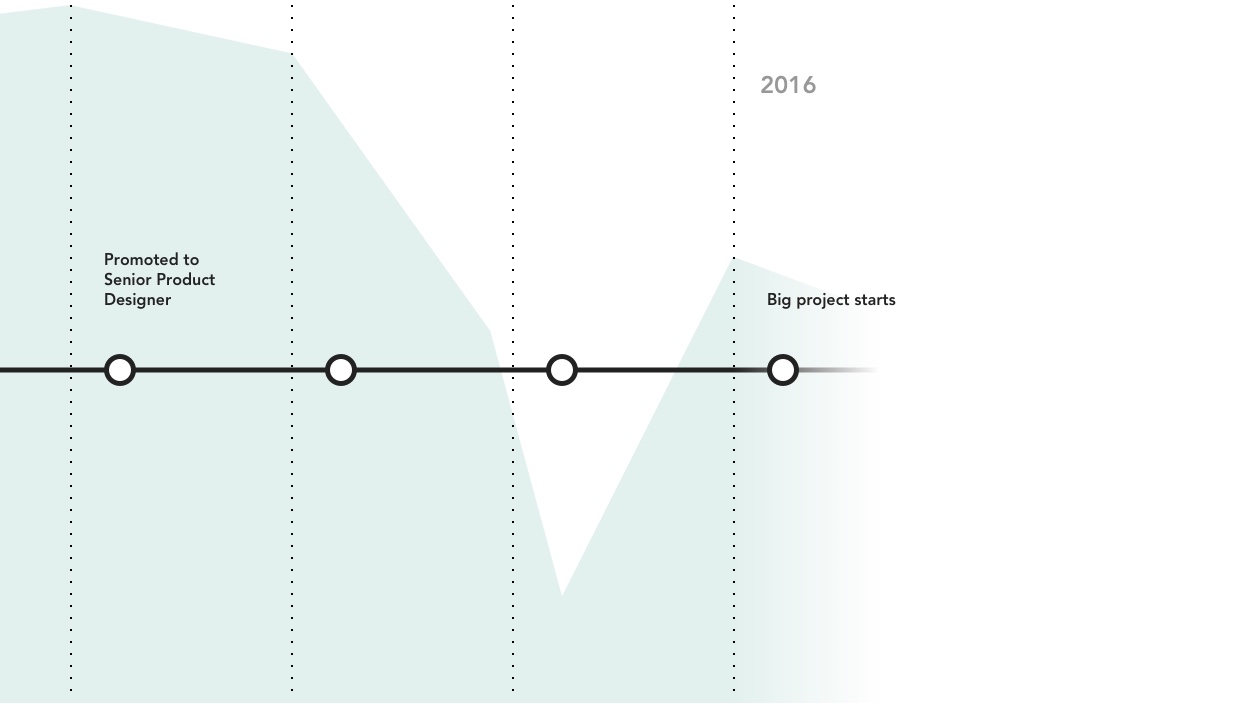

Challenge: A completely unmanageable workload

In 2016, my team was working on the hardest and most complex UX problem I had ever encountered (and still probably is, to this day). It was over a year’s worth of work. And it was being timed with another big launch, so there was extra pressure.

Well, we were so focused on building these tools for the web that at one point we realized that we also needed to do the work in the app so that we didn’t totally break everything when we launched.

To get this work done in time, we quickly spun up another squad of engineers to focus on the functionality for the app. So, I suddenly found myself the only designer for two squads, one designer to 15 engineers, working on the hardest design problem of my life. I very quickly became very overwhelmed. Yet, for some reason, I was so afraid to tell my manager that I was struggling with the workload and quickly burning out.

Why was that? A few reasons:

- I remember thinking a lot about my title, senior designer, and that part of being senior was handling increasingly complex work. Well, this was harder than anything I had ever done, so I assumed this must be what being a senior designer was like.

- I like working on complex projects, and I know that I’m good at it. But I was worried about what it would mean about myself if I thought this project was too much work, or too complex.

- Also, I’m really hard on myself. I hold myself to high standards. And I’m bad at asking for help, and even recognizing that I should be asking for help.

This was the first time maybe ever where I felt positively incapable of doing the work. Not because I wasn’t skilled enough. But because I didn’t have enough time to do it. It seemed like the only way to execute on the massive amount of work on my plate was to find some way to duplicate myself.

One day, I finally broke down into tears and admitted to my manager, Jason, that this project was too much work for me and that I just wasn’t capable of doing it. I had been holding this in for months.

Anything that culminates in a nervous breakdown? Bad kind of challenging. Of course, nothing bad happened when I admitted that I couldn’t do it. Jason was like, I’m sorry that you’ve been going through this and felt like you couldn’t speak up about it. Let’s brainstorm ways that we can try and lighten your workload and get you some support. It was such a relief to know that my manager knew I was struggling. I felt like this huge burden that I had been secretly carrying was lifted. And, of course, I didn’t get in trouble for admitting that I couldn’t do something. My senior title wasn’t revoked. But, boy, was it reflected in my yearly review from that time. All of the comments were like, she’s doing a lot of good work but… is she okay?

“Jessica could focus her development on being more open about her needs and challenges… she is able to execute on a ton of work in high pressure situations… but I think Jessica could better express when she feels like she has too much on her plate… and making it clear with her product and engineering teammates if she needs help.”

Asking for help isn’t admitting weakness. If anything, I’ve learned that it’s a sign of maturity and self-awareness to be able to say that you can’t do something. It’s especially hard when you’re struggling with things that are close to your core identity of who you are. I self-identified as someone who was good at complex projects and was really good at managing my time. Struggling with this project didn’t make those things less true.

One good outcome of this was that I became more comfortable giving feedback on project scope and setting boundaries for what I can and can’t work on. When we were staffing the next round of projects, I helped Jason understand which projects needed one designer and which were too big for just one person. I helped call out areas where scope might creep and where we’d need more explicit support.

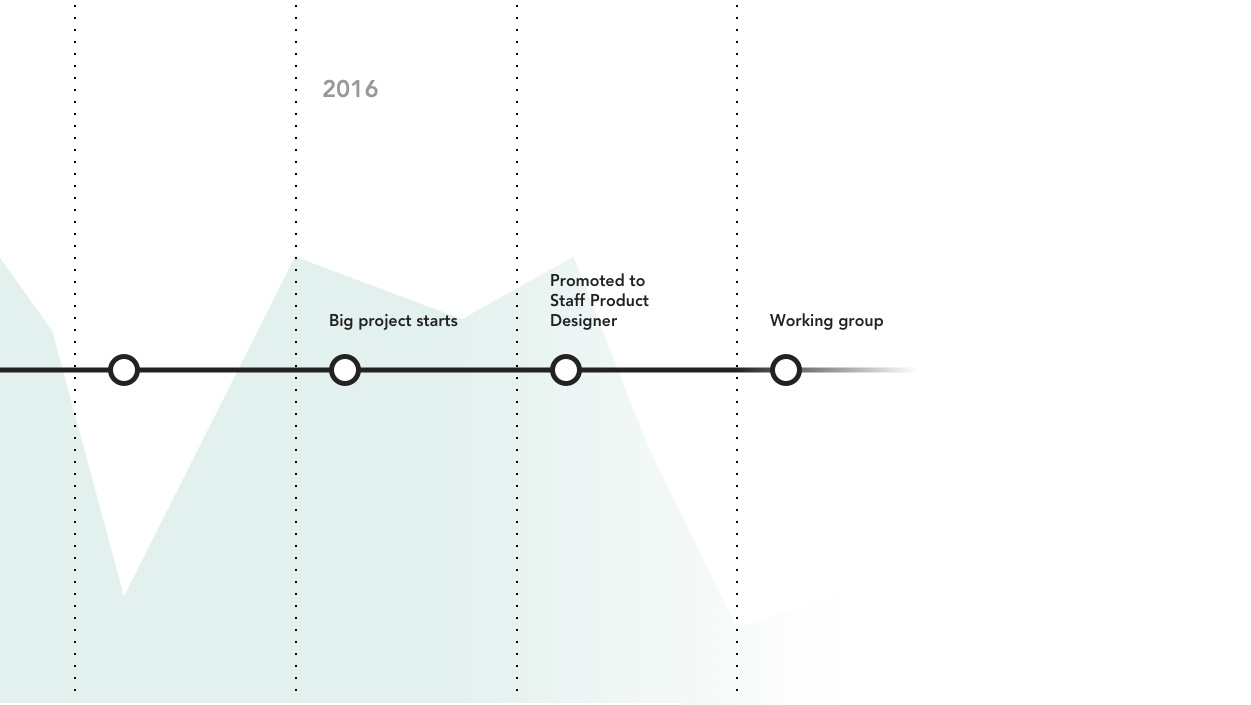

Challenge: A totally dysfunctional working group

Toward the end of 2016, my manager put me on a working group that was a mix of 5 or 6 staff designers and design managers: the most senior people on the design team. Our goal was to assess all of the disparate patterns being used across the experience and align on which patterns we felt should be used. It was a great mix of a few things that I love: design systems, documentation, and working groups.

A few meetings in, and I quickly recognized a couple of things that weren’t working. First, there was no one person in charge. We were all really senior, but without clear expectations for our roles, we were each sort of doing our best to lead and make decisions simultaneously. As you can imagine, we ended up arguing with each other a lot and making very little progress. Because the roles weren’t clear, there were a few managers doing IC work for the working group, which created even more confusion about how we were supposed to be working and what our roles were. On top of all of this, I was the only woman in the group, and that started to exhaust me over time.

Slowly but surely, this work completely drained me. On paper, it was right up my alley and something I loved doing. But the working group itself was completely dysfunctional. It got to the point where I would have to focus all of my energy on not crying during the meetings; I was constantly on the verge of tears.

I remember reaching out to Daniel, a staff engineer whom I really admired, and asking him, if you’re IC4 (staff), are you allowed to quit things? Are you allowed to just be like, I don’t want to do this?

I don’t give up on things easily, but I was so sick of crying and feeling anxious all the time. I finally went to my manager and was like, I’m sorry, this is not like me, but I need to quit this working group. I know you asked me specifically to join this group, but please, just take me off of it.

This was definitely the bad kind of challenging. Jason asked me to outline all of the issues I was seeing with the working group so he could address them. We went through each issue point by point, and to his credit, he fixed every single one of them. He totally rebooted the group, asked me to continue participating, and the reboot ended up being much more effective.

I ended up turning the list I made of everything going wrong with the group into a post on the Etsy Medium blog about the elements of an effective working group. The whole situation sucked, but I have a much stronger opinion on how to effectively work as a group: a clear facilitator. A clear, measurable goal. Clear roles.

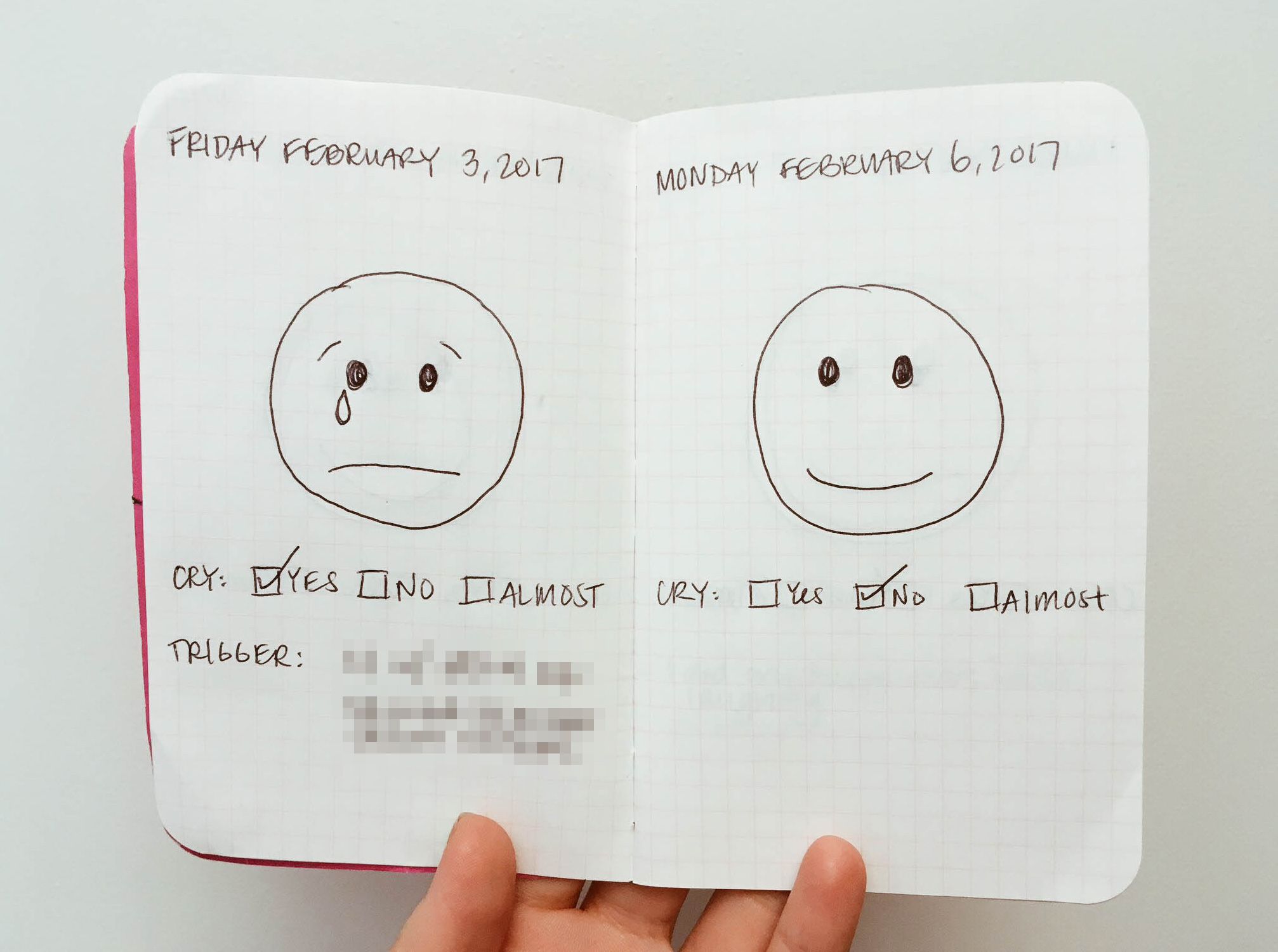

This is the situation that ultimately sparked my crying journal. I was crying so often that I started a journal to keep track of whether I cried each day, and if I did, what the trigger was. Tracking this helped me unpack my feelings around what was frustrating me and why. I also wrote a blog post on my personal website about the experience of crying at work and shared it broadly. Three years later, people still tell me that it made them feel more comfortable with their own emotions.

Again, this ended up being a bad situation for me. It sucked to go through. But boy, did I learn a lot…

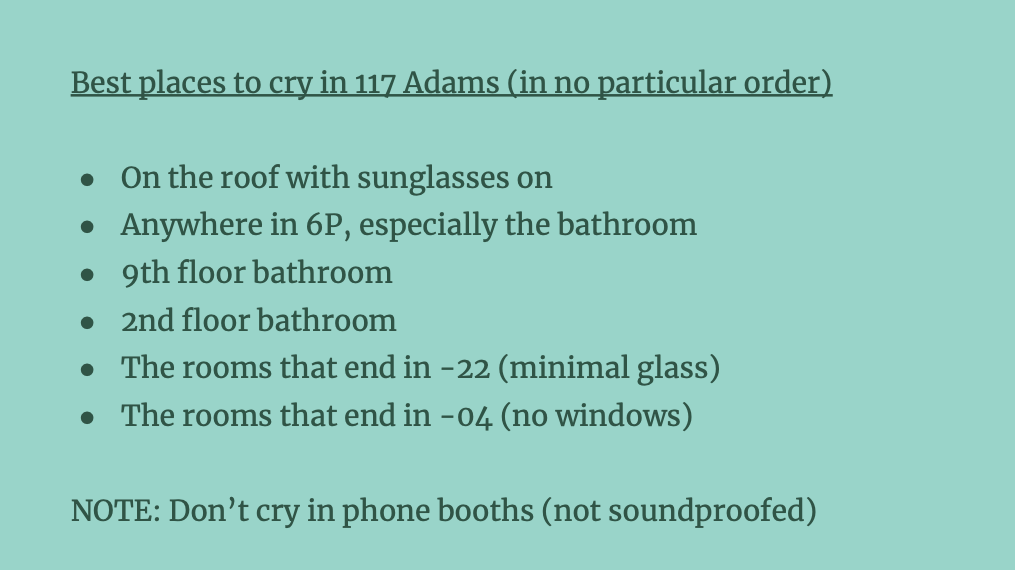

… including learning the best (and worst) rooms to cry while you’re in the office.

Challenge: Pivot to a project I’m not invested in

In 2017, I was working on a project that I really believed in, so much so that I had originally advocated for my team to work on it. But then the pre-holiday panic started to set in, and my team was told to switch projects to something different. I was heartbroken.

We were told to build an end-to-end feature that would require our team to work on the buyer side. In my 3.5 years at Etsy, I had barely touched anything on the buyer side.

I spent the first week of the project feeling grumpy. Like, really grumpy. I thought about leaving. But then at some point, I realized that I had zero control over the situation. There was a tight deadline; we had to ship everything before the holidays, so it would be a quick project with an end in sight. I decided to just power through it.

Well, the more we dug into the work, the more I became interested in it. The feature was going to affect numerous flows and features across Etsy. I had to think through what we wanted to show people on the buyer side, and what kind of information we needed to collect from sellers to make that possible. It was my first time really thinking about Etsy as an intricate system, where one thing over here affects something else over there. I spent a ton of time talking to other designers and asking for their advice on how to approach the work. I had no idea how to run experiments or how to think about the many different states of the checkout flow. But there were a ton of people around me who did, so I focused my energy on learning as much as I could from them.

To my surprise, this project ended up being the good kind of challenging. I learned so much. And I felt really good about our execution of the work.

Looking back, it gave me the experience that I needed to have more of an impact at Etsy. Teams had been really siloed between buyer and seller at the time, so it was rare to have the chance to own an end-to-end experience. I went from being somebody that was an expert on building seller-facing features to someone who could think across the buyer and the seller experiences.

It also helped me form a stronger opinion on the best way to structure teams at Etsy. Thinking about a feature holistically, instead of just about the buyer-facing work or the seller-facing work, wasn’t just rewarding. It led to higher quality work.

Ultimately, as you might know, the project was not successful. Not enough buyers or sellers wanted the feature, so it wasn’t really impactful. But! Some of the most powerful stories and learning opportunities can come from failure. Months later, I was able to turn this project into a story for others to learn from; I presented about this project at the Operating Team offsite, which was a really cool opportunity.

Overall, I’m really glad that I worked on this project; I ended up getting so much out of it.

Challenge: Try a totally different way of working

In early 2018, we kicked off new work on our team. At the time, I remember feeling a little bored, and a little lost. While I was glad the previous project was over, I was also coming down off the high of learning something completely new. I was back to working on listings, and while I loved that work, I also remember wondering if I had learned all that I could learn at Etsy.

Well, a few months later, our team was told to switch focus to a new track of work. And not only were we going to deliver product changes with this new track of work, we were simultaneously going to pilot a completely different process for building products at Etsy.

It was really, really hard at first. One week, I was feeling super confident as a staff designer, and like I had learned all that I could learn. The next week, I felt like I had no idea how to do my job. I had been following the same process, more or less, for years. I had gotten really good at it. But now, there were times when I was just not sure what my role as a designer was supposed to be. It was so jarring. And that feeling lasted for a solid six weeks.

But then at some point it clicked. And wow, it changed my entire outlook on how to do my job. And what the role of design is. I don’t know how to describe the feeling, other than it’s like being nearsighted and being able to see the things right in front of you, but then you put on glasses and suddenly the things that are in the distance come into focus, too. And you realize that there was this whole part of the world around you that you were just not looking at or thinking about.

This was definitely the good kind of challenging. I think this work is one of my favorite examples of something that ended up being the good kind of challenging, but it wasn’t always clear that’s where things were going to go.

It felt really hard, but we also had a lot of agency over the way we operated. It also felt really stretchy. I had to get used to the feeling of not knowing the answer. It was super humbling. Once I became comfortable with not knowing, I spent a lot of time asking questions, reading articles, and talking with my teammates about what was working and what wasn’t.

We also weren’t held to a GMS goal. Our entire focus for the first few months was on learning and developing this process. So we felt safe trying things that were a little bolder, and we felt safe failing. Every day, our team was coming up against things that we didn’t know how to do, but we felt like we were able to problem solve and figure it out.

I think it’s also funny to look back and think about how naive I was to think that I had learned all I could learn about process. It really makes me excited to think about what I still don’t know.

Challenge: Try a totally different role

This is all pretty fresh, so even though I’m still sorting through all of this, here’s my best attempt at zooming out and reflecting. At the end of 2018, Eleonora proposed an idea for a new role for staff designers at Etsy, called Design Lead. Normally, the design manager is accountable for the quality of the work of their reports. This new role would shift the accountability to the design lead. The advantage of having a design lead is that, because they’re ICs, they’re closer to the work and would be able to give higher quality feedback. Her plan was to pilot this role for the apps team for six months.

One thing that we talk about a lot in the staff design group is what career growth looks like for higher level ICs that don’t want to become managers. It’s not very well defined, and part of that might be because there aren’t a lot of examples out there that we can point to for guidance. I was looking for more responsibility, but as an IC, I didn’t know what that could look like. I felt like I could have a larger impact than I was having, but wasn’t sure what that could mean as somebody who didn’t want to be a manager and who still wanted to design.

When I heard about Eleonora’s role proposal, it sounded like exactly what I was looking for. So I asked to pilot this role for six months as well, with a few modifications. One key difference between our proposed roles was that El was going to be working across all of the app squads, and I still wanted to stay embedded on a product squad while performing design lead responsibilities.

Two weeks after my new role started, I went on sabbatical, which was pretty unfortunate timing. The last week of my sabbatical, I was so nervous about coming back that I cut off all of my hair in an attempt to at least look like someone who was confident. (Yeah… real talk.) When I came back, I spent the next few months struggling like I’ve never struggled before, and it was really hard to untangle why.

A lot happened while I was out, and I needed to quickly get caught up on all of the work so I could start giving feedback and making recommendations. I felt like I was constantly running around and reacting to things, instead of having the space to be proactive. There were a lot of new skills that this role required that I just didn’t have practice doing. I’m used to directly solving problems, instead of focusing on enabling others to solve their own problems. I found it really hard to measure the impact I was having. Plus, I had my own design work to take care of, which I loved doing, but I was struggling to give it the attention that it deserved.

I couldn’t tell if I was overwhelmed because of sabbatical, because of the new role, or both. I started recognizing some of the warning signs from past experiences: a workload that was only possible if I came in early and left late. Unclear roles and expectations. Crying in 1:1s. And the feeling of being stretched so thin that I started to feel like I was failing at everything.

This was the bad kind of challenging. But confusing, because this was a role that I really wanted to take on, and I was afraid of what it would mean about my career opportunities if I admitted that things weren’t working.

One amazing decision that my manager and I made was that I should get a professional coach, which is basically like going to work therapy. I had originally planned to ask the coach for advice on leadership and building influence. Instead, when I showed up to our first meeting, I was like, “I need your help figuring out if this role is even right for me.” We talked for an hour, and at the very end, she was like, look. It sounds like you’re trying to do two jobs at once. And you’re not set up for success.

I started crying. I felt so heard. And like it was okay that I was struggling, and that it wasn’t my fault. I had been so hard on myself. It helped me realize that if I wanted to make this role work, I’d have to seriously adjust the scope of the role, or give up my day-to-day design work. I wasn’t interested in giving up design work. But after a few attempts at adjusting the scope of the role, I decided that this was just not the right situation for me to be piloting design lead.

As you now know, I hate saying no and admitting that I can’t do something. But I felt really at peace with finally admitting to my manager that I didn’t want to do this role anymore, and I wanted to go back to just doing my regular ol’ design work.

We had a retro at the six month mark, focused on identifying the situations in which design lead makes sense and when it doesn’t. It actually ended up being a really interesting experiment having me and El try out two different iterations of the role. Because of this, I think we ended up having a better understanding of how we might ensure that future design leads are set up for success.

Here’s the full journey map! Pretty wild.

Ok, so reflecting back on all of these examples, what are some things that they had in common?

Good kind of challenging:

- It’s not easy, but it’s not terrible

- The learning that I’m doing aligns with my goals

- I feel supported and safe

- I have a certain amount of control over the situation

- I come out the other side grateful for the opportunity

Bad kind of challenging:

- I feel stressed, overwhelmed, and anxious

- I’m not set up to succeed

- A lot feels like it’s out of my control

- Everything builds up to a breaking point

- I’m just grateful that I made it out of that situation

The confusing thing about a bad situation is that I’m still learning. It’s not as simple as, am I learning, or am I not learning? You can see how in some bad cases, I was able to really make the most of the situation. And after the fact, I’ve always learned something. But the process for getting to that point doesn’t usually end up worth it.

Beyond becoming really self aware, how can you learn to identify these situations sooner? Here are some concepts, tools, and frameworks that I’ve found to be helpful when reflecting on whether challenges are good and bad.

Identify gravity problems

For the past few months, I’ve been in a book club with Kristen and Erin. We’ve been reading this book, Designing Your Life, which is all about using the design process to create the life that you want to live. There’s a ton of activities, and it’s totally cheesy but great.

“You can’t change gravity… Just accept it. When you accept it, you’re free to work around that situation and find something that is actionable.” – Designing Your Life

In the book, they talk about this concept called a “gravity problem”. Gravity problems are things that you just can’t change. They’re out of your control. They’re a circumstance, not something you can act on. You either need to accept it and embrace it, like I ended up doing in the case of [the buyer-facing project], and when my friends started leaving. Or you need to realize that there is nothing that you can do, like in the case of [the project that was too much work]. I couldn’t duplicate myself. And the timeline was not going to change. So I needed to adjust my expectations and find a different way to solve the problem, instead of hoping that more time was going to appear out of thin air.

As the book says, an important part of the design process is reframing the problem, and only then can you truly develop multiple solutions to whatever you’re facing.

Identify what’s energizing, and what’s draining

One important factor in a good challenge is whether the things that you’re learning are aligned with your goals and interests. This can require a ton of self-awareness, which can be really hard to have in the midst of a challenge.

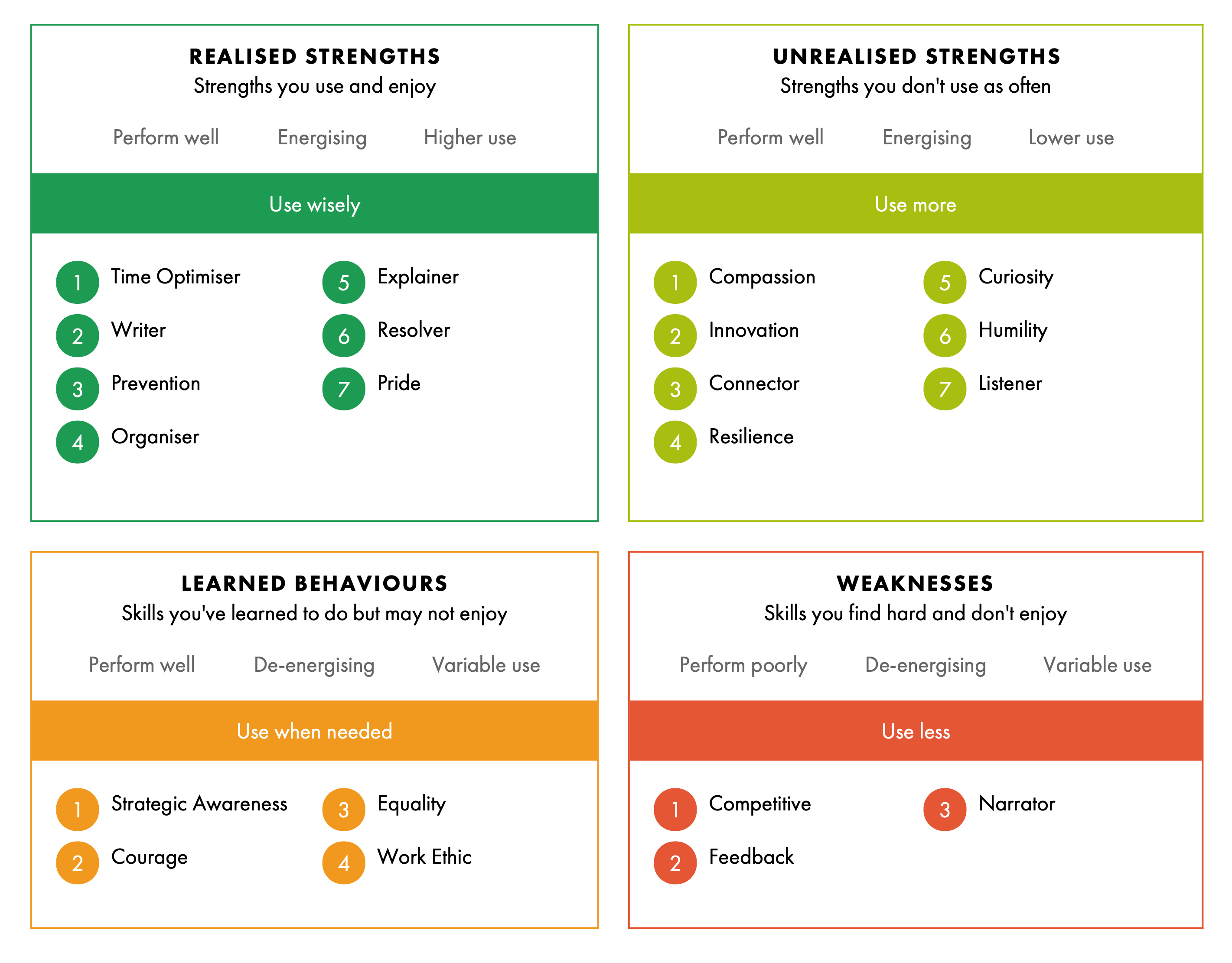

There’s a strengths test called Strengths Profile that all of the staff designers and design managers did at the beginning of the year. This one’s mine. According to Strengths Profile, there are things that energize you, which are the top two boxes here, and things that drain you, the bottom two boxes. I’ve done similar tests before, but what I really love about this test is that they aren’t afraid to acknowledge weaknesses. This framework says that instead of focusing on our weaknesses, we should spend our time on the things that energize us, and learn to maximize them, and even use them to work around our weaknesses. I love that it gives people permission not to focus on the things that are draining, and also acknowledges that everyone has things they aren’t good at, and that’s okay.

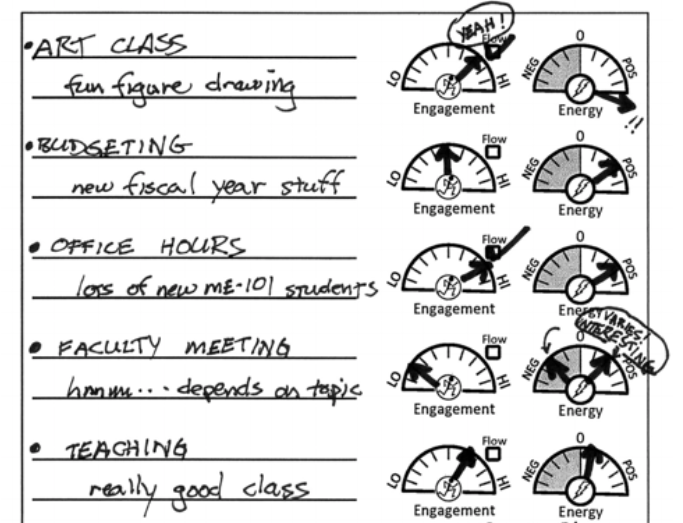

I also love journaling as a way to identify patterns and unpack your feelings. In Designing Your Life, we tracked our day-to-day activities, how energizing or engaging they were, and whether we entered into a flow state. This is a sample from the book. While I was doing the design lead pilot, it helped me realize how I was spending my time, and that the things I found most energizing weren’t my design lead responsibilities. It reinforced that I still really loved day-to-day design work, and that I shouldn’t give it up.

Reflect on whether you’re set up for success

Sometimes, there is no way in which you were going to succeed at whatever you were trying to do. The reality is that sometimes these things are completely out of your control. I’ve found the concept of “being set up for success” extremely helpful, not only for my personal challenges, but also in thinking about the success or failure of projects that I’ve been on.

If you’re set up for success, you have all of the support and structure in place to do your job well and to succeed. But the impact of those things not being there can be detrimental. As someone who tends to blame myself, or put unreasonable pressure on myself, it can be really hard to recognize whether I’m set up for success on my own. This is where I’ve found talking to a trusted group of friends, or an unbiased third party like a coach, to be really really helpful.

I read a lot of management books because a lot of the skills needed are actually really similar to the skills that senior ICs need as well. Lara Hogan, former Etsy engineering director, has this concept of a “manager voltron” which, to me, doesn’t need to just apply to managers. The idea is that you can’t expect to get everything you need out of one person, and so you should be building a trusted network of advisors that can help you work through different kinds of situations.

Eleonora and I had biweekly one-on-ones as we were going through the design lead pilot so we could compare notes and give each other advice as peers. I don’t think I would have had my ah-ha moment about design lead not working out without the input of a coach. When I was struggling with the working group, I reached out to Daniel, who was in a different org than I was but at a similar level, to help understand expectations for my role. And I’m constantly talking to Erin about all kinds of problems that I’m having.

Practice saying no

One of the hardest skills that I’ve had to develop is the ability to say no. I want to spend my time in the good kinds of challenges, and avoiding the bad ones. The bad ones are not worth it.

At first, not only was I afraid of saying no, I wasn’t sure if I was allowed to. Which sounds ridiculous, but this is how my brain works. Practicing saying no to smaller things, like participating in a working group, made it easier for me when it came time to saying no to things that felt higher stakes, like taking on a different role.

Find or ask for sponsorship

Finally, we can’t talk about challenges and growth without also talking about sponsorship.

Managers, the best thing that you can do for your reports is sponsor them. Recommend them for opportunities that will push them and stretch them. Because you’re managers, you have access to opportunities and information throughout the company that ICs just don’t have access to. We can try and weasel our way into stuff, but at some point, because of the nature of an org structure, we hit a ceiling.

I was lucky enough to have many, many opportunities for growth here at Etsy, and most of them were because I had a manager who recommended me for that opportunity. Those managers made it their mission to help me grow and develop skills. And sometimes, when those opportunities pushed me beyond my limits, they made it their mission to help me work through those challenges. I cannot emphasize enough that in addition to finding your reports these opportunities, you also need to make sure that you’re supporting them throughout, and that they know that you’re supporting them.

My time at Etsy has been full of good challenges and bad challenges. At times it’s been really hard, but it’s been so, so rewarding. I’ve learned so much. Thank you for letting me learn and grow in such a safe and supportive environment.

So, speaking of challenges, it’s time for me to dig into a new challenge, a new set of problems, and to push myself to really grow. I’m hoping that leaving Etsy will be the good kind of challenging for me. But, it’s time for me to take my own advice: I can’t know unless I try.

Thank you.

Posted Nov 12, 2019